Pause carousel

Play carousel

Karen Renaud is a Professor of Cybersecurity at Abertay University.

Influencing people to behave in a particular way is surprisingly hard.

Spare a thought for King Henry VIII of England during the 16th century. In those days, people would urinate against the walls of his castle. The resulting smell was unpleasant, to say the least, and the King and his entourage often had to move to a new castle when the “miasma” became unendurable. The King instructed his servants to paint large red crosses at the smelliest spots, hoping to dissuade urination, thinking that people would not dare to urinate on a religious symbol. This did not work - instead of being dissuaded, they seemed to relish having something to aim at.

Funnily enough, in recent years Schipol airport in Amsterdam painted a fly inside their urinals to give people something to aim at. In this case, the intervention was successful at reducing spillage.

King Henry VIII’s red crosses could reasonably be considered a medieval version of what Thaler and Sunstein call a “nudge”. Since their Nudge book was published in 2009, a number of governments, including the USA, the UK and Australia, have established units to find nudges that can be used to change uncooperative behaviours. The idea is that the nudge is a small manipulation of the “choice architecture” that aims to prompt people to choose the course of action the designer wants them to take. The choice architecture is simply the environment within which the choice is made. Yet, as King Henry VIII found, changing behaviours by manipulating the context (finding an effective nudge) is harder than it seems.

One of the most intractable behaviours in cyber security is the prevalent use of weak passwords. Hackers exploit weak passwords to get into people’s accounts to carry out their nefarious activities. When the need for passwords became ubiquitous, information security practitioners thought that if they disseminated password policies explaining what a strong password looked like, and mandated these, this would solve the problem. The implicit assumption was that people didn’t choose strong passwords because they didn’t yet know what a strong password looked like. The policies did not make much of a difference. This meant that bridging the knowledge gap, on its own, did not guarantee a change in behaviour. Another idea was to issue people with strong passwords, to take human choice out of the equation altogether, as it were. The problem then was that people couldn’t remember these complex passwords, so they wrote them down. The strong passwords quickly lost their strength, meaning that intervention did more harm than good.

As the nudge technique became increasingly popular, we started looking at choice architecture manipulations that might persuade folks to choose stronger passwords. Researchers had already experimented with the display of password strength meters to show people, as they typed, how strong their passwords were. This effort, once again, built on the assumption that if people knew what a strong password was, they would use one. Some researchers reported that these meters made passwords stronger, but others found that they didn’t make much of a difference.

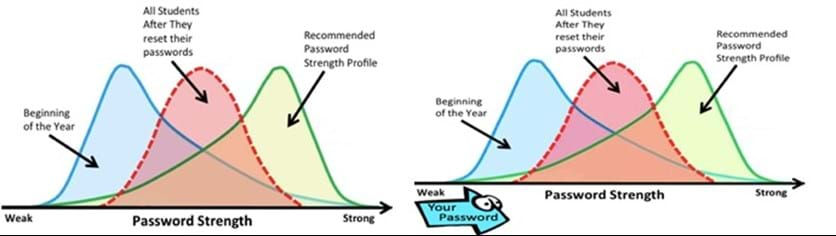

Over a three year period, we experimented with a number of visual “nudges”, which were displayed when people were in the process of choosing a password. For the first two years, we simply displayed a range of different pictures above the password entry field, including a password strength indicator. Two of the nudges are shown below - both exploit the expectation effect. The one on the right superimposed an arrow that moved across the bottom of the graph as they typed, reflecting the strength of their password. Yet another displayed a pair of eyes above the password entry field, hoping to make people aware of the risk of someone else getting hold of their password.

None of these was effective - the overall password strength profile did not budge. In the third year of our study, we found a nudge that worked. What we learnt from our failures was that strong passwords are costly - they take longer to type and are harder to memorize. This means that people have no incentive to choose a strong password because we are all, by nature, cognitive misers. People will always choose the path of least resistance - that’s just how we are made. A simple visual cue nudge did not have the power to overcome this tendency.

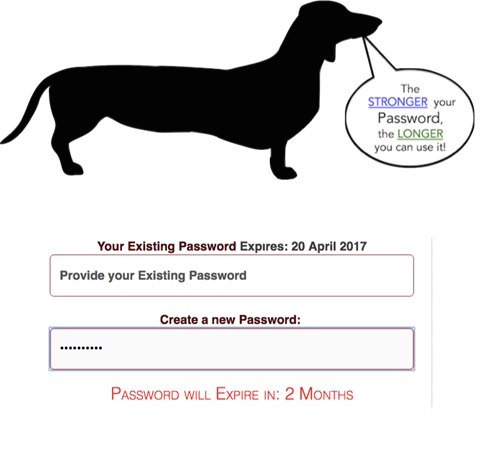

So, we designed more power into our “enriched” nudge: we offered our participants an incentive to choose a stronger password: the stronger their password, the longer they could keep using it. We manipulated the choice architecture by displaying the wiener dog shown below to make sure people got the message. As they typed, text displayed just below the password entry field told them how long it would be before the password expired. For example, the password “123456” would only be valid for 2 weeks, whereas a good password like “I ate 8 marshmallows at the BBQ” would only expire after 6 months.

In effect, instead of merely trying to nudge people with a visual cueing nudge, we actually offered them an incentive. After six months with the enriched nudge on the password choice page, the overall password profile of the entire group was significantly stronger.

However, we do not believe that this nudge ought to be widely adopted for every possible account. It should only be used when something of real value is being protected, like a bank or email account. Strong passwords are costly, so we should do our best to help people match the strength of their passwords to the value of the asset it projects. This means that we have to ensure that the asset being protected is worth the time and effort required to manage the strong password.

Nudges do not address the root cause of weak passwords: human memory limitations. Henry VII’s problem disappeared when indoor plumbing became universal. While people have to remember their passwords, the tendency to choose weak passwords will persist. Hence judicious deployment of nudges for important accounts is the wiser option than widespread usage, which is likely to backfire.