Pause carousel

Play carousel

Pythons, moths and frogs exhibit a certain type of camouflage that hides their identity from other animals even after they have been spotted, new research has found.

The study, by Abertay University and the University of Stirling, challenges the theory that a predator immediately recognises its prey as soon as they see it.

Published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, the research reveals that the appearance of animals with “edge-enhanced disruptive colouration” – where dark patches of camouflage have darker edges and light patches have lighter edges – is difficult for others to identify.

The findings show, for the first time, that this pattern of colouration – which gives the impression of varying surface depths and shadows – appears to slow the process of recognition and, consequently, makes animals harder to identify.

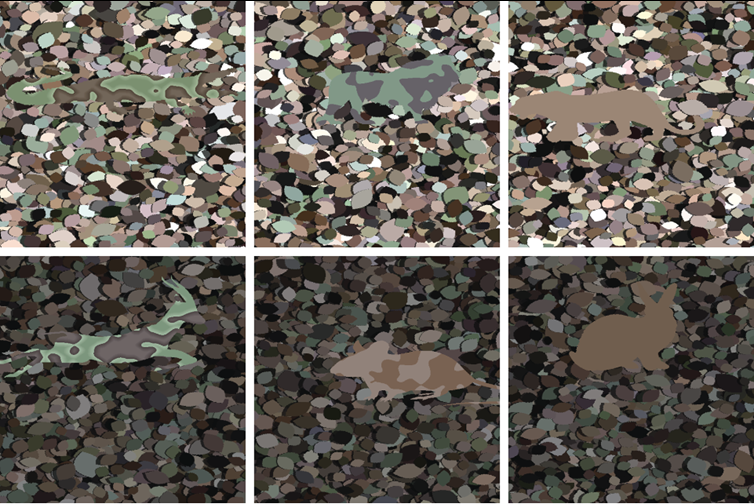

(Images used in the research at Abertay's Visual Perception and Camouflage lab)

The study was conducted by Dr George Lovell, a Lecturer in Psychology at Abertay; Dr Rebecca Sharman, a Research Fellow in Psychology at Stirling; and Stephen Moncrieff, a BSc (Hons) Forensic Psychobiology student at Abertay.

Dr Sharman said: “In the past, it has been assumed that if you can detect where a target is, you must also know what it is. For the first time, we show that this is not the case.

“Edge-enhanced disruptive colouration not only makes targets harder to find, but also harder to identify: just because you know where something is, does not mean that you know what it is.”

Researchers conducted tests with human volunteers at the Visual Perception and Camouflage Lab at Abertay. The participants viewed images of camouflaged animals on a monitor and were asked to locate the target and identify it as either predator or prey.

The research team observed that participants required longer to identify a target, even if they located it relatively quickly.

In addition, when the image background was simplified – making all animals equally easy to locate – it still took longer to identify those with edge-enhanced disruptive colouration.

Dr Lovell said: “The theory that disruptive colouration might impede recognition has been part of biological textbooks for decades. It is great that we finally have some experimental support for this claim.

“Developing effective camouflage has obvious military applications, but it is also used for town planning, architecture, fashion, conservation, and bird-watching, amongst many other things.

“Surprisingly, most military camouflage is not developed on the basis of empirical evidence and, as such, research of this kind has the potential to really make a difference to the safety of personnel.”

Research from Abertay’s Visual Perception and Camouflage Lab uses a range of techniques, from visual psychophysics to virtual reality, video games and behavioural studies with animals.

To view the paper in full visit http://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-25014-6